Coming Soon: Story Magic in Projects

With Projectkin, my goal has been to encourage families to share their stories—in ANY form. An untold story is a story lost. In a new talk on 14-Nov, I'll share the magic project thinking.

This gives you a preview of my talk on Nov. 14. Join us, won’t you?

Project Thinking

As you do your genealogical research to capture the facts of your ancestors’ lives, narratives spill out. The narrative threads of stories help us understand what we’ve learned and connect us to our community and place in history.

Stories, however, aren’t just a reiteration of facts into a logical stream. They capture the moment and spark your imagination — and curiosity. Looking into the history of technology, you can see how we’ve continuously tried to apply innovations to the stories in our family history.

Consider stereography, desktop publishing, or home movies. Looking back, you can see how family history experiments pushed new media forward. What started with rub-on letters zoomed past desktop publishing to blogging platforms, streaming video, computer vision, javascript, and AI.

I waded into my family history after a 30-year career riding technology waves. First, I wanted to update the material I’d inherited and add my own spin. Next I started to think about what a modern spin even meant.

Today, we have so many inspiring ways to capture, preserve, and share our stories that we can get lost in the various media types and platforms. Worse, the incentives of platform vendors can be at odds with our goals of preserving stories for future generations.

How often have you been eager to dive into a project — because you can. You might tell yourself it’s a “proof of concept.” Did you test the result? Did you continue the experiment? Is it something more now?

At Projectkin, we think a lot about generational storytelling in this technology-saturated world. Today, we have many options to produce stories but little encouragement to source, preserve, and contextualize our work. Doing so takes a mind shift that changes the effort from technological experiments to exercises in storytelling.

We’ve graduated from an infatuation with technology and are ready to make it work for us. It’s time for a mind shift.

When we tackle a story as a project, we’re free to consider the right technology to serve a specific purpose. We can focus on the quality of the work — and the workflow that will maintain the final output.

The magic — and challenges — of projects

Modern projects can be magical, but they also create challenges. Will the result of the effort produce an object or artifact that can be passed down to future generations? Will digital artifacts be meaningful—or even readable—in the future? Examining the stories and artifacts our ancestors left behind can help us anticipate how our project work will affect our descendants.

Since our start, we’ve been privileged to have

, a personal archivist with decades of experience join us for a monthly talk. In her Kathy’s Corner series, she shares insights on the safest ways to preserve artifacts passed down to us as heirlooms. Those mementos, photographs, recordings, and printed materials are imbued with history. Our modern tools let us extend the life of these artifacts by preserving originals and using digital copies to explore their stories. Creatively remixing digital versions lets us revisit the family narrative with modern sensibilities.Consider, for example, an elder retelling their lived memories of historical milestones, or movements.

A generation ago, that story might have been captured in a printed and published book or perhaps a personal letter. Today, ordinary people have ready access to the technology to record the elder on video then combine their storytelling into an

edited video that contextualizes the story with digitized photographs of the places, people, and things they’re describing.

a live slide show program that combines the elder’s voice with photos and artifacts and an interactive discussion with family members.

a self-published photo book that includes collage-based arrangements of photographs with descriptive text.

a self-published booklet, article, or blog post including a written narrative shared in a newsletter with extended family members

A simple story can be modified in endless ways to suit available time, budget, and objectives.

Don’t shoe-horn a story into a platform:

Find platform(s) to fit the story

Too often, platform companies push us to share stories in ways that fit their platform. That’s reasonable; they’re selling a platform. They’ll make the task easy, fun, and inexpensive. While those are important benefits, I encourage people to step back and focus on the whole problem they’re trying to solve.

Take the example of a family history calendar as a Christmas gift. Do you want to create a family history calendar, or are you doing that because this platform makes that fun and easy? What’s the real goal? Is it a shared family history context throughout the year? If they use the platform to create the calendar, is it preserving the source materials and the final output? How does it help with the real goal?

Ask yourself: What’s the problem you’re trying to solve? Only then can you find a good fit in a technology and approach that fits the problem.

Projectkin’s Project Recipes were designed to help family historians become more comfortable with new storytelling forms without compromising genealogical principles. With each recipe, you’ll see that we try to present storytelling solutions that:

Preserve artifacts and organize digital archives.

Add to a family narrative with material from reliable sources.

Are truthful to the facts and honest with citations.

Use standards-based digital forms with open access so that future generations can use it as the basis for their own projects.

Be long-lasting, using archival-safe materials for production.

Platform independence lets us explore tough questions about purpose, archiving, and backups. These are the kinds of questions that many technology vendors skirt past as inconvenient or irrelevant to their revenue goals.

Are stories genealogical facts?

Since the first cave paintings, we’ve manipulated stories to fit our communications objectives. We simplify, amplify, or expand on our tales to suit our audiences, their literacy, and their interests. Why would it be different for the stories that capture and share our family history? It isn’t. It can get complicated even if our goals are to be truthful and separate facts from fiction.

Hundreds of years ago, when only a few had access to books, archives, and source documents, history was a rarified field. As documentarians, scholars could be trusted to capture facts consistently and preserve them for history. We see a long tradition of genealogical work done to the standards of academic scholars. Peer review through historical and genealogical societies created a means to maintain standards.

As literacy and publishing access expanded to individuals and families, these formal standards fell away to creative storytellers and voracious readers. The contemporaneous facts captured in the hand-written letters, sketched family trees, and marginalia on photographs become fodder for our family stories. Truth wasn’t always a priority.

With the dawn of desktop publishing in the 1980s and then the web in the 1990s, storytelling expanded with new forms of media and engagement. In the 21st century, social media, streaming video, and generative AI have pushed media formats even further. Collaborative trees, at-scale digitization, and DNA analytical techniques entered this landscape to revolutionize access to genealogical records.

Everything Looks Like a Nail

Family storytelling can—and has—benefited from all of these new media forms. The problem is that we get so excited about new technologies we want to use them. It’s a fancy new hammer. We start looking for things we can do with this new toy. Newness alone can make it fun.

The problem is compounded when editorial material in websites, blogs, and newsletters gush about the tool when platform vendors offer financial incentives.

It’s hard to focus on the problem when you’re smitten by the tool.

The answer lies in community.

The good news is that we are not doing this alone as family historians. While we draw on our families for heirlooms, documents, and anecdotes, a community of fellow travelers is here trying to do the same thing with their kin. Working together, we can lean on one another for best practices, insights, and sanity checks.

Let’s take a simple example from a decor blog-worthy afternoon project: Framing and adding old family photos to a “family tree wall.”

It seems like a fun home decor project, and it is. But — when you look at such a project as an effort at family history storytelling, you realize there’s much more to it.

Don’t lecture: Elevate, support & encourage.

It’s easy to slip into outrage and the castigating language of a convert. Instead, I recommend you stay focused on the goal. Remember the problem you’re trying to solve.

If you also want families to preserve their inheritances of artifacts, then help them. No one should be castigated for hard work. Help them digitize their favorite pieces. Ask them why they’re important. Show them how originals might have been damaged in earlier generations (and how to prevent further damage by preserving originals and only displaying copies).

I formed Projectkin to encourage families everywhere to share their stories. I’d seen how a community could inspire me. As a community, we have shared powerful stories and improved on each other’s ideas. Contextualizing stories and unwrapping secrets is hard work. Our Projectkin community multiplies the available inspiration, investment, and support.

Through events, conversations, and articles, we won’t just suggest projects like “family tree walls.” We’ll help each other with ladders and measuring tape. We share insights for using the display to inspire younger generations with accomplishments or engage them with QR code-linked questions and comments.

New Media Isn’t New to Family History

Consider how we engage in storytelling traditions around holidays, birthdays, weddings, and anniversaries. We’re already working on the creative magic of projects to celebrate special occasions. Sometimes, these are done on our own as amateurs. When the budget allows, we bring in the talents of professionals.

In virtually all cases today, these projects leverage modern digital technologies for convenience and economy…

Rehearsal dinners or wedding receptions include slide shows of the celebrants as babies, young children, and lovebirds.

Life story videos are screened at memorial services.

Bespoke photo books and biographies are lovingly produced as gifts at milestone anniversaries and birthdays.

Websites and family archives capture a family story for public or private exploration.

We often consider creative projects like these to be on a continuum. On one end are expensive, special-occasion gifts, and on the other are simple, disposable crafts. While the forms may have changed, I expect this continuum has been consistent across the ages. Our challenge today is unleashing creativity while maintaining the discipline of preservationists’ workflows.

Mindset and Magic

When you think of family history stories as projects, magic happens. The key difference is in mindset. When you treat these kinds of projects as contributing to the fabric of your family history, you’ll take the time to find the best media available to tell the story. You’ll also explore your genealogical records to get the facts right, archive the digital artifacts, document sources, capture the context, and preserve the project final in archival forms for future generations. It doesn’t matter whether the project was a photo calendar or a feature-length film.

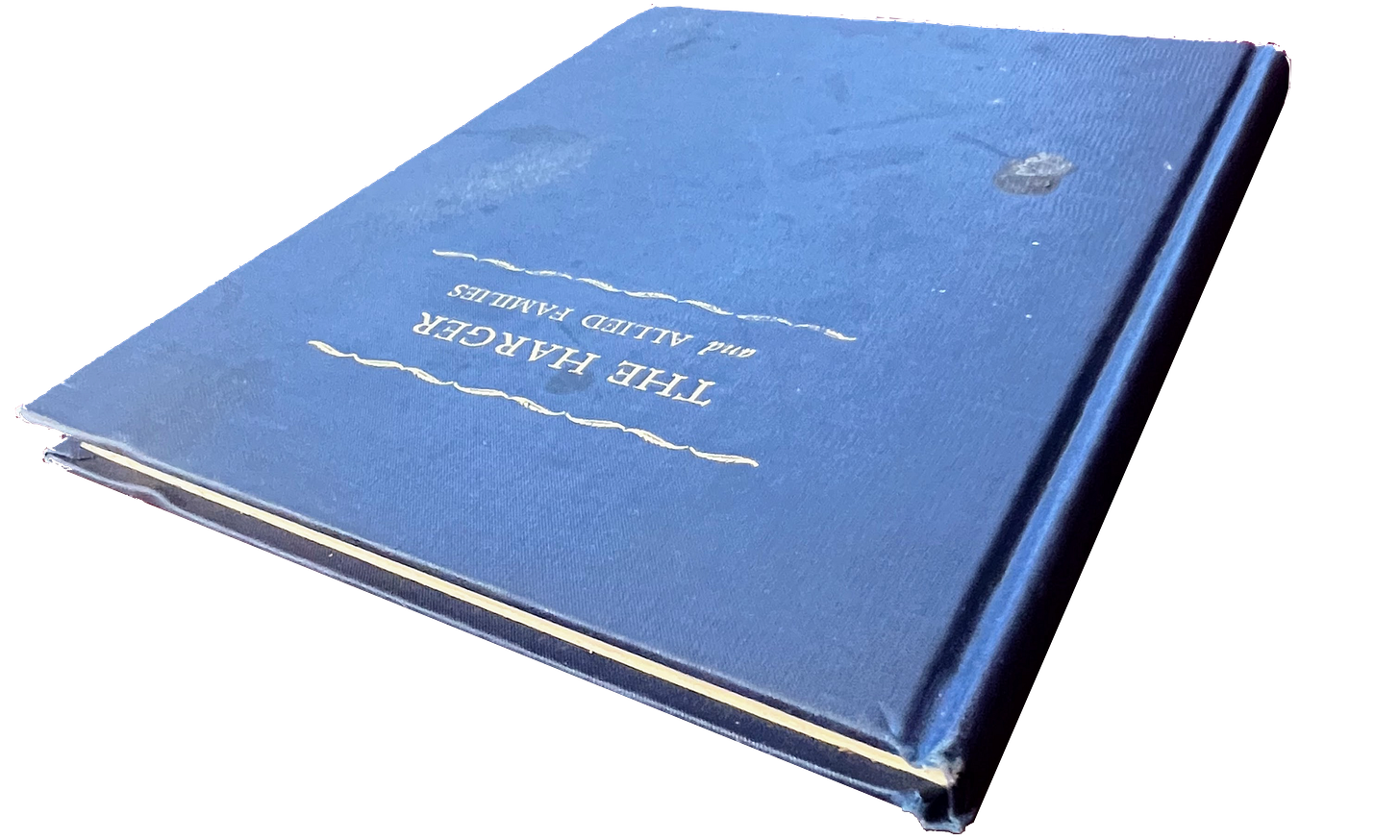

As I shared in a “My Sixteen” post, my cousins and I were fortunate to receive a beautiful family history narrative my grandmother wrote and self-published in 1948.

The book is very much in the tradition of the 19th and early 20th-century family history books she drew on for resources. It includes long discussions of lineage, skips over inconvenient truths, and focuses on the positive messages one would want descendants to remember. In a memorable line, my grandmother describes her husband’s Victorian grandmother, Mary Sering Jaques.1

“She had high ideals which she instilled into all her children and was both thrifty and very generous. She helped her neighbors in want or illness and she and her husband ‘met all life's tasks marvelously’ as her daughter said.”2

I expect it was also written with its living audience in mind, a half-dozen or more of whom were lineage society members.

Family history storytelling has a job to do

Sometimes, the purpose of a story is not obvious. It could be as simple as conveying facts. How those facts are conveyed can say a great deal. On occasion, it’s a formal responsibility for celebration or memorialization. In the case of the Ancestor Wall, it might simply be to brighten up a dingy corner.

Planning, designing, and executing a project starts with being clear about goals. Planning around quality standards, timelines, and budgets has a remarkable way of forcing the articulation of unspoken priorities. By keeping your goal in mind, you can focus on the near-term goal while deferring other elements for a later project.

For example, you might have a project to deliver a memory book as a means of therapy for an aging elder3 struggling with the symptoms of dementia. While collecting background, you may put an effort into capturing your loved one’s memories in recordings so that they might be useful archival footage for future projects.

The original recordings may be uninteresting to the generation that heard the voices growing up. A decade or two later, such recordings of an ancestor’s dialect may be fascinating to a new generation. Projects may be designed for the benefit of the kids, but it’s okay if it takes them years for descendant generations to unpack the context and meaning.4

Storytelling is too important to be glossed over, trivialized, or ignored. There isn’t one best project or story. You’ll also likely create many projects; no one of them will be your life’s work.

Let’s explore this together: Join me for “Story Magic”

Join me in a live talk on November 14 and add your voice to the conversation. The program is scheduled for 10 AM PT, 1 PM ET, 5 PM GMT, 19:00 CET, and 7 AM NZDT on November 15.

I hope to inspire you to capture and share your family stories with your family and future generations. By registering, you’ll get a personal link you can use to join the Zoom event.

Like all Projectkin events, it’s free and independent of platforms. We don’t allow sponsorships or affiliates, and our modest expenses are supported entirely by voluntary contributions.

More about Projectkin

Projectkin is a community for family historians of all ages, skills, and interests. We meet in an online forum hosted on Substack and at virtual events hosted on Zoom to share ideas, projects, and inspiration. We’re hooked on stories that will engage our siblings and children in the stories of our shared past. We’re also intensely platform-independent. We don’t accept affiliates or sponsorships and only accept modest “coffee” contributions to help support our operational expenses.

See her seated 50th-anniversary portrait in My Sixteen post.

Mary Sering’s daughter was Elizabeth “Lizzy” Jaques whose scrapbook became a key source for the “Harger & Allied Families” book and my family history research.

Jude Rhodes’s project recipe for Memory Books for Memory Loss provides a wonderful example.

Consider, for example, words shared at memorials in the middle of the AIDS crisis when gay partnerships were not always understood or appreciated by family members. Sentiments may have been shared using coded language that spared the sensibilities of the elderly while conveying meaning to younger generations.

So much to unpack and think about here Barbara. Looking forward to the discussion

The timing won't work for me, but a new player has arrived in the form of family history podcasts using NotebookLM. For now they're only two American voices, but that's OK. They can be a little biased and hallucinate, (as with all ai), however with some customisation, it can be quite entertaining. Maybe it's a way to share a short snippet of your family history to the non genealogy family members.