When Mom went into hospice in March 2022, my siblings and I had a pretty good sense of how we wanted to handle her remains. In 2014, we moved her from her home in Honolulu to a memory care community very near me in Berkeley, California. Soon after her husband Harland died, it was clear that dementia had its grip on her and that it would be impossible for her to live alone.

I brought her to California under the ruse of a “visit.” Eight years later, as we would drive the same route nearly every day, she would marvel at the California sky, “no clouds in the sky.” From a recording on August 15, 2021.

The dementia had made it difficult for her to carry on a conversation. Driving made her feel less debilitated. It only took a few words to convey an idea.

I learned to hear it as poetry.

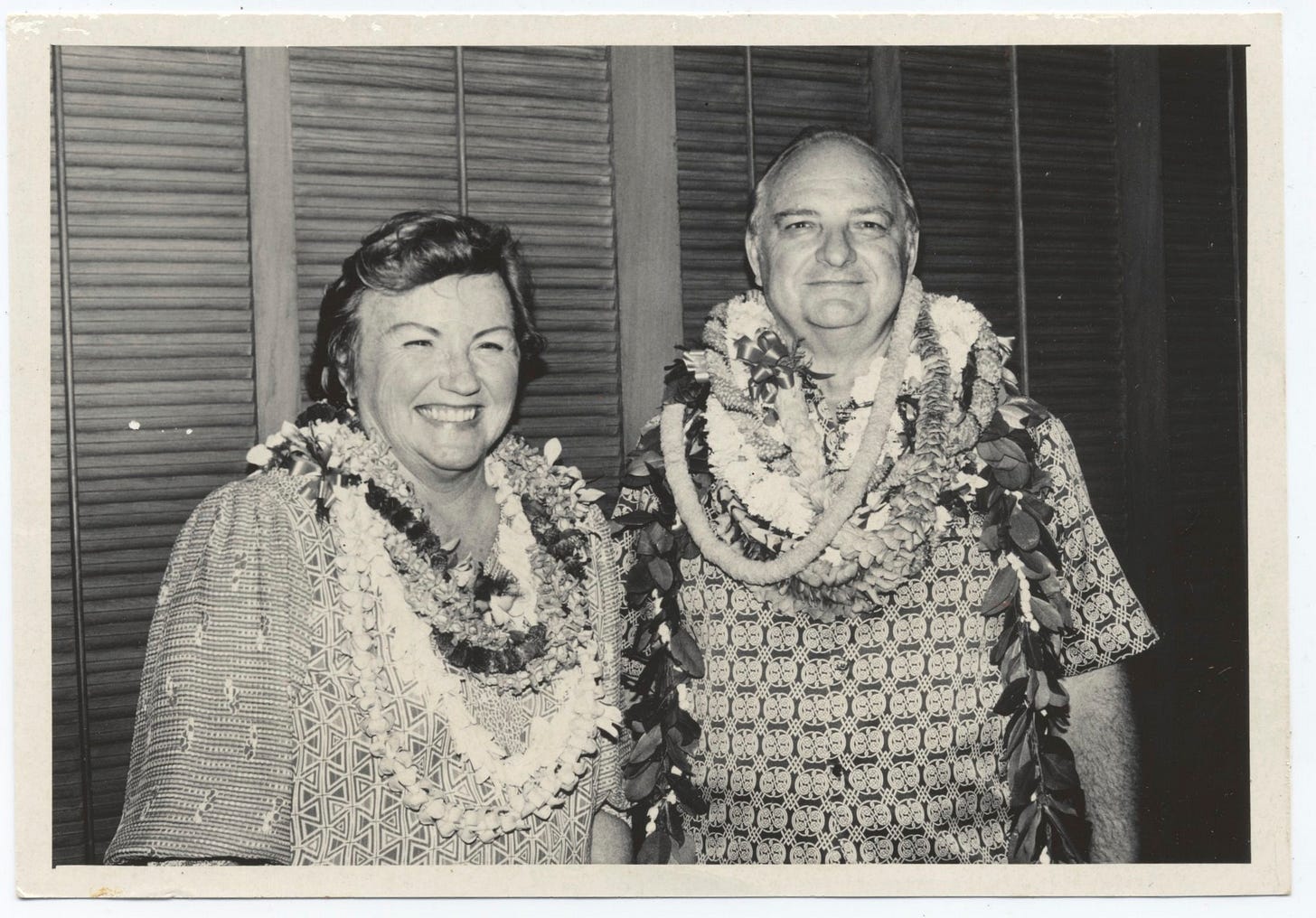

We hadn’t had a chance to talk about final arrangements. She’d agreed to have her second husband, Ed, cremated after he passed suddenly in 1989. He had been the love of her life. His death came very suddenly after a meal of contaminated crab on their last business trip together to the Philippines.

She was a wreck after he passed. He had progressed from feeling poorly to a coma within days. She was still recovering from a scheduled mastectomy that had been delayed so that she’d be able to go on the trip.

As her adult children, we had flown across the country to be with her for the surgery. Now we’d returned. Delaying the services wasn’t practical. The details must have been a blur to her as her network of friends stepped in to arrange for his remains to be cremated, a memorial service at a chapel, and an ad hoc ceremony to release the urn with his ashes into the ocean off Waikiki. We said our goodbyes with leis and remembrances.

Her recovery was slow but steady. She’d never been alone. Going to the movies without a date was unimaginable. She also knew how to be charming.

Her Dance with the Captain

Soon she found companionship through her work at the Chamber of Commerce and her local Rotary Club. It was the cruise ship dating scene that clinched it. By May 1997, she married a retired Navy captain and JAG officer. Harland and his late wife had traveled the world and raised a family in Australia. They connected like a two half-hitch knot. Cruising the world together, they cared for each other until he passed in 2014.

As a retired JAG officer, he had the legal chops to have their separate wills and trusts updated when they married. Harland specified that should he predecease her, she would have the option to be interred with him in his niche at Punchbowl National Cemetery, a special privilege his rank afforded him. In updating the wills, the logistical detail of his first wife’s ashes didn’t come up. At the interment, that awkward fact became clear. There isn’t room in a military niche for three.

Aloha 'Oe, Aloha 'Oe

When Mom passed, we all knew that she would have wanted to be laid to rest in Hawaii. After leaving her childhood home in Chicago, she’d always made travel a part of her life. It started with the glamorous Mad Men era of New York. As the flamboyant redhead, she was accustomed to being the center of attention. Her complicated love triangle made an escape to Latin America reasonable. On a return to United States, relocating to Honolulu seemed an obvious move because it was as far from New York as possible.1

That was 1968, less than a decade after the territory had become a state. Mom went on to make Hawaii her home for another 46 years as my sister settled nearby and raised her family. Soon, Mom had grandchildren and great-grandchildren to call her “Tutu,” a traditional Hawaiian term for grandmother. She loved it, signing cards and emails with “22.”

A Transition on her Terms

Though her dementia had been slow, the final transition came very quickly. Two months after an unrelated condition triggered her entrance into hospice, she was gone. The last weeks were incredibly painful for her, and I felt nothing but relief.

She was ready.

When Mom died, my brother was in Washington, D.C., and my sister, in France. With our extended family and friends spread from Australia to Europe, it made sense to consider an online celebration. The lingering pandemic still made travel and large gatherings risky.

To make it work, we dispensed with formalities and celebrated her life over Zoom. There were no officiants, no program; my siblings and I just winged it. She would have approved. The centerpiece was a film my sister and her filmmaker husband put together with old photos organized around the timeline of her remarkable life.

We went into the event blind. None of us had ever been to a Zoom-based memorial, and we didn’t know what to expect. I used my startup-burnished email marketing skills to queue up notices and manage the Zoom configuration. I built a website to serve as a temporary memorial. Three years later, the film is a treasured memento. The materials from the website have informed my writing for my stories here and on my private publication for my cousins.

To my surprise, the greatest gift has probably been the remembrances shared in the Zoom recording. They were unscripted, unplanned, and wholly authentic.

May to September

As a family, we knew Mom’s final resting place should be in the waters off Waikiki, as close to Ed as possible. It just felt right. The dear friends who had arranged for the boat in 1989 were gone now. This time, we had options.

In 33 years, Hawaii tourism had prospered, and the procedures for a burial at sea are well established. On September 24, 2022, we gathered as a family for a memorial week on Oahu. We shared meals, told stories, and took one last boat ride with her on the waters off Diamond Head.

A catamaran charter boat easily held the twenty of us for a sunset cruise from Kewalo Basin to Diamond Head. We all accepted my sister’s uncanny visual memory to triangulate the rough spot where we’d released Ed’s ashes over 30 years earlier.

We tossed dozens of leis, orchids, and other flowers into the water, said a few words, and dove in. Though initially it seemed grim, the local practice of swimming in the water as you let a loved one go was beautiful. The Neptune Society had specially prepared and wrapped an organic box for her ashes. My nephew brought fins and goggles to carry the box to the ocean floor. As he came back up, we all cheered in celebration.

Like laughter at a memorial, you don’t expect it, but it’s beautiful when it happens.

A few days after our service, my nephew returned to the coordinates shared by the cruise operators. He wanted to check on the box, and the GPS coordinates made it easy to find. This time, his GoPro captured the little puffer fish and a lei of seaweed that seemed to protect it, nestled into the coral on the ocean floor.

Thursday marks three years since she passed on May 22, 2022. On reflection, that seems pretty perfect.

May Tutu be with you, always.

We don’t have a tombstone marking the spot. In time, the box will decompose, and the ashes will be dispersed into the ocean sand. I have the coordinates, the photographs, and the memories. Our unconventional choices for memorializing and celebrating her life seemed like the only sensible option during the pandemic.

Our two online and in-person memorial events mirrored a traditional funeral and burial service. The film and recorded Zoom event captured her life story for us to treasure privately. We never published an obituary. Her passing was formally recorded through our city health department and county recorders.

Are we missing anything as we invent memorial forms for a new generation?

Are we inventing new commemorative forms? I honestly don’t know. In our case, I’m confident that our twist on the ceremonies gave us the salve we needed for our shared grief.

I also confess that a part of me wants to apologize to future genealogists. I can see them cursing in my mind’s eye. I can only hope the trail of documentation, archives, and stories I leave behind will more than make up for it.2

Like many of you, I had Mom’s story and other pandemic experiences in mind when I participated in Jane Hutcheon’s remarkable six-part series of interviews for Projectkin, “Forget-me-Not: How We Memorialise.”

This thoughtful series, the fantastic cemetery explorations on Substack3, and a little time have all given me the confidence to revisit our decisions. I’m still very comfortable with the decision and have realized how important our archived stories are in filling the role played by obituaries and tombstones.

Did the pandemic times change how you celebrated memorials? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Family Endnote

Family members mentioned in this story:

Lois Harger Parker (1929-2022)

Edmund W. J. Faison (1926-1989)

Why exactly remains an unfolding story.

I’d not previously realized how this may be some of my inner motivation behind Projectkin.

Jane Hutcheon, David Shaw and Christopher Padgett, I’m looking at you, 😉