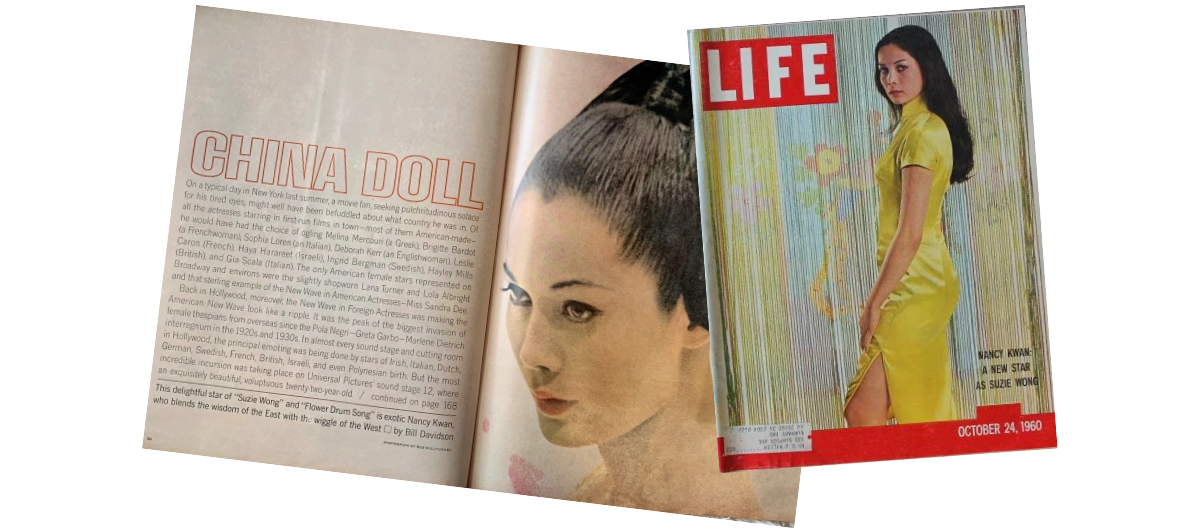

The Architect from Kowloon & his Famous Daughter, Nancy Kwan

Kwan Wing-hong, a Cambridge-trained architect, known during the War by his code names shares a remarkable history shared by his famous daughter, the legendary Hollywood starlet, Nancy Kwan.

Our guest, writes for and joins us for this All About That Place cohort of the Projectkin Members’ Corner. Monthly posts from members celebrate their contributions to family history storytelling — in all its forms. Posts may be written or recorded (audio or video) will be shared for free each month. Explore the entire Members’ Corner here.

An Exhibit Unwinds the Story.

This unusual story combines Hong Kong with Hollywood stardom and WWII-era spycraft. It came together after a conversation with Nancy Kwan, the legendary starlet of post-war films like the 1961 Flower Drum Song.

I’d known Nancy since I was a teenager in San Francisco in the 1990s. In 2024, she visited an AAPI History Month exhibition I’d arranged at the Bob Hope Patriotic Hall in Los Angeles.

The exhibit took us deep into her remarkable family and their contributions to Hong Kong in the last decades of the Qing dynasty.

The story starts with this famous photograph of a young Dr. Sun Yat-sen, with his contemporaries, Chan Siu-pak, Yau Lit, and Yeung Hok-ling, taken at a medical school in Hong Kong around 18881. Standing behind them is Nancy’s uncle, Kwan King-leung. A copy of this famous photograph is on the cover of a book, “The Beginning of the Colony of Hong Kong and the Kwan Family,” co-written by another of Nancy’s uncles, S. Kwan.

Colonial Hong Kong Sets the Stage.

Nancy’s father, Kwan Wing-hong, was a member of an affluent Chinese family. His family sent him to Cambridge University to study architecture. While there, he met and married a British fashion model, Marquita Scott. After graduating, he returned to Hong Kong with his new wife and moved into a large home in Kowloon. They had a son, Ka-keung, and a daughter, Ka-shen (better known by her English name, Nancy.)

By the time his daughter Nancy was born in May 1939, China had been at war with Japan for eight years. Most Chinese date the start of the war to the Mukden incident in Manchuria in 1931. As international affairs deteriorated, so did their marriage. By 1941, Marquita Scott divorced her husband and returned to England. After his first wife returned to England, Kwan Wing-hong married a Chinese woman named Nan.

The Chinese who lived in the territory of Hong Kong under European control were protected from the hardships of those wars. However, that was not to last.

The Japanese coveted Southeast Asia's natural resources. Before WWII, the Kwan family owned vast tin and rubber holdings in Malaya, which thrust family interests directly into the war.

Black Christmas & the Escape from Hong Kong.

On 7 December 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on US forces in Hawaii. Attacks soon followed against other Allied Pacific bases. The British had been complacent and underestimated the ability of the Imperial Japanese forces. The loss of two British battleships and the fall of Malaya and Singapore upended the British strategy in the Pacific. The battle of Hong Kong is considered one of the first campaigns of World War II. The Hong Kong garrison of British, Canadian, and Indian forces fell in 17 days, surrendering on 25 December 1941.

It’s a date known in Hong Kong as “Black Christmas.”

The British had no practical way to defend the city. In a 1962 interview. Kwan Wing-hong recalled how Hong Kong was “chaotic and disorganized.” He added:

“I knew all of this would change as soon as the Japanese occupation authorities arrived, so I decided that it was now or never if I was to escape with my family. I booked passage on a Japanese ship that was leaving for the Portuguese colony of Macao, about forty miles down the China coast.

On the morning the ship was to sail, we left our beautiful house on the hill in Kowloon. There was Nan and myself and our cook and the children’s nurse. We had the two children hidden in baskets, which the cook carried Chinese-style, on a pole across his shoulders. We had nothing with us but the clothes on our backs, so as not to arouse suspicion. I’ll never forget that day.

“We walked past platoons of Japanese soldiers, took the ferry from Kowloon to Hong Kong, and boarded the Japanese ship without any trouble. The Japanese were stopping all families with children and baggage; but since we were well-dressed and didn’t appear to have either, I guess they couldn’t conceive that we were refugees. I tried to act as imperious as I could, and maybe they thought I was a Chinese collaborator leaving on some official mission with a retinue of servants.”

Kwan Wing-hong and his family reached Macao without incident. He realized he could not support his family on that island. He negotiated with a Chinese businessman and arranged passage for his group on a junk headed up the Pearl River to the Chinese mainland.

The junk was a blockade runner, jammed with rich and poor people. Nancy’s father’s description continued:

“Little Keung and Nancy kept crying, but there was scarcely room to stretch out and sleep. We sailed for nine hours in the pitch darkness, to avoid the Japanese patrol boats. When we finally arrived, our ordeal was far from over. The area was teeming with Japanese soldiers. I knew I had to get about a hundred and sixty miles inland, beyond the area the Japanese army controlled, and I decided to brave it by walking right through them. Again I used my rich-Chinese-collaborator act.

Using my small reserve of money, I hired two sedan chairs, with porters to carry them. Nan rode in one and the nurse and the children in the other. The cook and I walked. We walked right through the Japanese army.

They just stared at us curiously as I strode by like a pompous functionary, although I was terrified lest they ask for my identification. They never did. I’m quite proud of that march. We walked a hundred and sixty miles in five days. That’s a little more than thirty miles a day – or just about the pace the British army sets when it marches under combat conditions in the field.”

The Intelligence BAAG in Wartime China

Kwan explained that he and his family lived in several places in China. Kweilin (Guilin), Chungking, and Kunming, near the Myanmar (Burma) border.

Nancy added:

“I was too young to remember all this...but my stepmother has told me about Japanese air raids and how we nearly starved and how my father was always going off on mysterious missions for the Allies”.

Kwan Wing-hong’s value to the Allies could not be minimized. He looked Chinese, but his soul was British. He was very well-educated, and his aristocratic heritage gave him the leadership abilities that helped him achieve results. It was probably inevitable that Kwan’s talents would find a place in the military. He joined an organization that came to be known as the “British Army Aid Group” (BAAG).

Lt. Col. Sir Lindsay Ride formed the BAAG after escaping from a Japanese POW camp. The War Office incorporated the BAAG into the structure of Military Intelligence known as Military Intelligence, Section 9, or M.I.9.

The BAAG became operational on 6 June 1942 and presented itself as a humanitarian aid organization. To be sure, it provided substantial amounts of aid to needy civilians. However, its primary mission was to help prisoners of war and internees escape. In doing so, it also collected military intelligence.

Chinese James Bond

Kwan Wing-hong’s language skills were critical. An American aviator forced to parachute into hostile territory must have been pleasantly surprised to be welcomed by a Cambridge-educated Chinese savior who spoke impeccable English. He might be viewed as having been a Chinese version of James Bond who led the oppressed to safety.

Kwan’s BAAG codename was “Domus.” He may have also been known as No. 74 and may have also used the following names: “Hunky” or “Hongkie.” According to available information, Domus worked in forward areas and mainly engaged in Escape, Evasion, and Evacuation missions, principally under Colin McEwan. Domus was said to be full of initiative and devotion. He later reportedly received the King's Commendation from Great Britain.

The BAAG continued its work after the surrender of Japan and was disbanded on 31 December 1945. As Colin McEwan2 explained,

“My man in the upper West River area rejoiced in the code name of Domus3 although after all these years I can find no reason why that particular christening came about. Hunky Kwan was a Malayan Chinese architect whom I had known in Hong Kong (sic) and many of my readers will have seen his daughter Nancy Kwan who became quite a well-known film star in post-war days.

My pet story of Hunky’s ingenuity was when Lt. Miller of the USAAF was shot down in Hunky’s area. There was a Japanese concentration camp in that particular area and since he had been shot down in daylight there was a fair amount of hue and cry after him which came a bit too close for Hunky’s comfort.

So, to pass a few days till this died down, Hunky took the lieutenant by night into Nanning, the biggest city in the area, which, sitting as it did on the West River, was a main Japanese center. There they both spent a few days in one of the better class brothels which catered for the higher ranking Japanese officers but on the ‘call out’ system which meant that no Japanese apart from the odd medical officer ever called personally.

In May 2024, Nancy recounted this fantastic story of her father’s World War II exploits in China. Although he began his work with the British forces, sometime after 1942, he transferred to the American forces and worked with them until the war's end. This fact was validated by discovering his original identity card/paper issued by United States forces in China in 1944. (Nancy recently found it in her family’s archives.)

A Little Girl’s Dress

At the war's end, American pilots thanked Kwan Wing-hong for his contributions in their own way. Nancy remembered how a group of American pilots came to their home with gifts for her and her brother. They presented her with a white dress made from parachute cloth and her brother with a little leather bomber jacket. Sadly, both of these items have been lost through time.

On the occasion of AAPI History Month, I arranged for Cindy Yee,4 Nancy Kwan’s friend and superfan, to present her with a recreation of the little white dress made of parachute cloth. The dress brought back all the emotions and memories of her father’s service in World War II.

The exhibition had been planned to celebrate the fallen warriors of AAPI heritage during WWII. Nancy’s presence also allowed us to explore her father’s unsung heroism.

As the first Asian actress to play a leading role in a major American motion picture, Nancy Kwan has a distinguished place in film history. Today, she’s working on her memoirs.

This post is part of our special All About That Place cohort for the Members’ Corner, but these posts are released each month. Our next opening is for October with a deadline of the 21st of the month. Do you have a story to tell? We’d love to share your work. Learn more:

Join Projectkin in the Members’ Corner

I brought Projectkin to Substack because of the rich community features of the platform. Three months in, our community has bloomed. We’re thriving with a focus on creative project ideas as a way to share our stories:

These young men became the “Four Bandits” to the Chinese government. It is credited with the plot to overthrow the Qing government and move towards a modern democratic China.

Colin Mitchell McEwan was born in 1916. He had a Master’s Degree in the classics from Edinburgh University. He joined the Colonial Service and arrived in Hong Kong in April 1939. He escaped to China on 25 December 1941. From “Colin McEwan’s ‘Diary’ - The Battle for Hong Kong and Escape Into China,” Dan Waters, Alison McEwan, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 45 (2005), pages 41-115.

In ancient Rome, the Domus was the type of townhouse occupied by the upper classes and some wealthy freedmen during the Republican and Imperial eras. That was an appellation worthy of an architect.

Cindy Yee describes her first meeting with the star:

“The first time I saw her I was 9 years old and was with a group of little girls waiting to be interviewed by the director. Nancy was rehearsing the scene “Grant Avenue “ in FDS. My dad took my little sister (6 or 7) who was in the parade scene sitting on the curb watching the parade and me to see the movie when it was released. When I saw the dance scene, I yelled out who was that because I remembered the dress rehearsal and thought she was absolutely gorgeous and someone who looked like me.

I lived in the San Fernando valley and grew up with white kids. Back then, there were hardly any Asians. I began following her career and relied on the LA Times Calendar section, the local Hollywood magazine racks and thumbed through them every chance I got, and Dr. Sue’s magazine racks in Chinatown collecting anything I could find on her plus watching all her movies and occasional tv appearances. I amassed an enormous amount of written articles and pictures in my big scrapbook.…

“Fast forward Sept. 15, 1979, my fifth wedding anniversary and playing poker with friends since we had a toddler. Around 8 pm I received a phone call from a very close friend who called to let me know that Nancy came into a Chinese restaurant for dinner. I asked for the address, handed my one year old to my husband, grabbed my scrapbook, and speeded down the 10 freeway. I door was locked! My girlfriend was able to get the door open and pointed me in the right direction. I knew she was shy and didn’t like to talk about herself, so i honored her wishes. Introduced myself and told her I was a hugh fan and asked politely for her autograph on my front cover. I was in 7th heaven and thought I would never see her again!

Fascinating story

What a remarkable story of Kwan Wing-hong and his daughter Nancy Kwan. Such courage & determination for this family after Hong Kong fell... Fascinating inspiring story.