How Can Family History Help People Living With a Dementia?

The aim is to have meaningful conversations. Those conversations can provide dignity and comfort to the sufferer, and practical and enriching engagement for their family and friends.

is a Registered Nurse in the UK and a qualified and professional genealogist at StoriesofOurGenerations. She’ll be giving a Project Recipe talk on August 8th, “Memory Loss, Conversations, and Family History,” register here (free).

As a Registered Nurse, I have extensive experience working with people and their families living with dementia and an excellent understanding of the available resources for researching a family’s history, including the ancestors, the community, and the local and national context of a time.

I have brought together these two professions of my career to create an approach that enables meaningful conversations when visiting and chatting with a person who is living with dementia.

Understanding the process of making memories and how they are stored and retrieved helps explain why the damage to brain cells affects memory in the way it does. New memories are much harder to make and store, and retrieval is compromised. I explain how old memories remain stored, enabling a person living with a dementia1 to retrieve these old memories.

My strategy for having a meaningful conversation with someone living with dementia is to focus on the older memories only and find triggers to recover them. The ideal way to achieve this is through relevant family and local history research about the person, their family, and friends. This background will then guide you in formulating prompts for conversations about their life as they lived it years ago.

What is a meaningful conversation?

A meaningful conversation is one where those involved are actively listening and cognitively engaged. Engaging in conversation requires the topics of discussion to be relevant to the participants. Finding common ground to sustain a conversation can be challenging if one of those in the conversation has memory loss and is disconnected from current events.

This is where family history provides the perfect solution to finding a topic for discussion that is both relevant and meaningful to the person living with dementia and their family. Why? Because it is relevant to the family regardless of their age and it is meaningful to the person because they can retrieve these memories of an earlier life.

Younger participants in the conversation will learn about the social and national history of the time discussed and more importantly, will learn about the life of their loved one.

To help those living with dementia using family history, it’s essential to study a specific timeframe—one that’s relevant to the person and their life. it’s usually best to focus on the time from their birth until they are about forty years old. Recent additions to the family are often not relevant or confusing to the dementia sufferer.

The FAN Method

FAN stands for Family, Associates, and Neighbours, and it can be very helpful for gathering material about a specific timeframe in someone’s life— particularly their early life and childrearing years.

The family includes the people a young person will have most likely met—grandparents, perhaps a great-grandparent, maternal and paternal aunties, uncles, and cousins, as well as their parents and siblings. Typically, these people will have been a part of their extended family during their formative years. Experiences with these family members will probably have anchored formative memories.

Associates might include friends from school, parent groups, and college classmates. You might also include mutual members of social groups, a church, and colleagues from work. Work often plays a large part of a young person’s life. Delving into the place of work, the type of work, and the colleagues can evoke numerous memories, many of which you may not have heard before.

Neighbours are the people in the community. Most people grow up in one house near other homes. Over time, they get to know the families who live nearby. When a person is young, the people in families nearby become a vital part of their lives. They bump into them on the way to the shop, when playing outside, or when a parent chats to the neighbours over a fence. This is often the earliest group of people a person meets and, therefore, has long-term memory attachment.

In working with clients living with dementia and their families, I often start by collecting what’s known about their life story. I use this background to research the family members and friends associated with my client’s childhood and early adulthood. Dementia often leaves memories of this period of our lives intact. They become memories that are retrievable with triggers or prompts. The method also applies to the physical aspects of my client’s life. I study details like the house where they grew up, their place of work, or the route they took to school.

What are memory triggers?

Triggers stimulate memory; this could be from a smell, a photograph or image, a place, or an object. If a person living with dementia is taken to a familiar place from their earlier life, it will trigger the memories of when they visited this place in the past; in contrast, taking a person living with dementia to a new place will provide no connection to the past and, therefore, no memory trigger.

Prompts can also help stimulate memory. For example, if someone talks about a past event during a conversation, this will help the person retrieve memories from the event. A meaningful conversation with someone living with dementia or memory loss can be a fun and comforting experience for all involved.

See my Project Recipe!

In my presentation for Projectkin, you will learn in more detail how you can engage in meaningful conversations with your loved one and how to manage these conversations and visits in a positive and fulfilling way.

Project Recipe: Memory Books for Memory Loss with Jude Rhodes

Conversations with loved ones suffering from cognitive impairment or dementia can be frustrating or even isolating. Professional genealogist and registered nurse Jude Rhodes of Stories of our Generations takes us through an approach she’s used successfully to trigger meaningful conversations.

I include some practical “DOs and DON’Ts,” and a project recipe. This method empowers the person living with dementia, bringing dignity and comfort to their otherwise confused world. It also provides practical and enriching engagement for their family and friends.

I’ve referenced “dementia” here because it is a general term for a decline in mental ability severe enough to interfere with daily life. It primarily affects memory, thinking, problem-solving, and language. It may also impact a person's control over their emotions. Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60-80% of cases, making it the most common type of dementia.

Hi Peter, thanks for your comment. I really look forward to seeing you on the 8th August

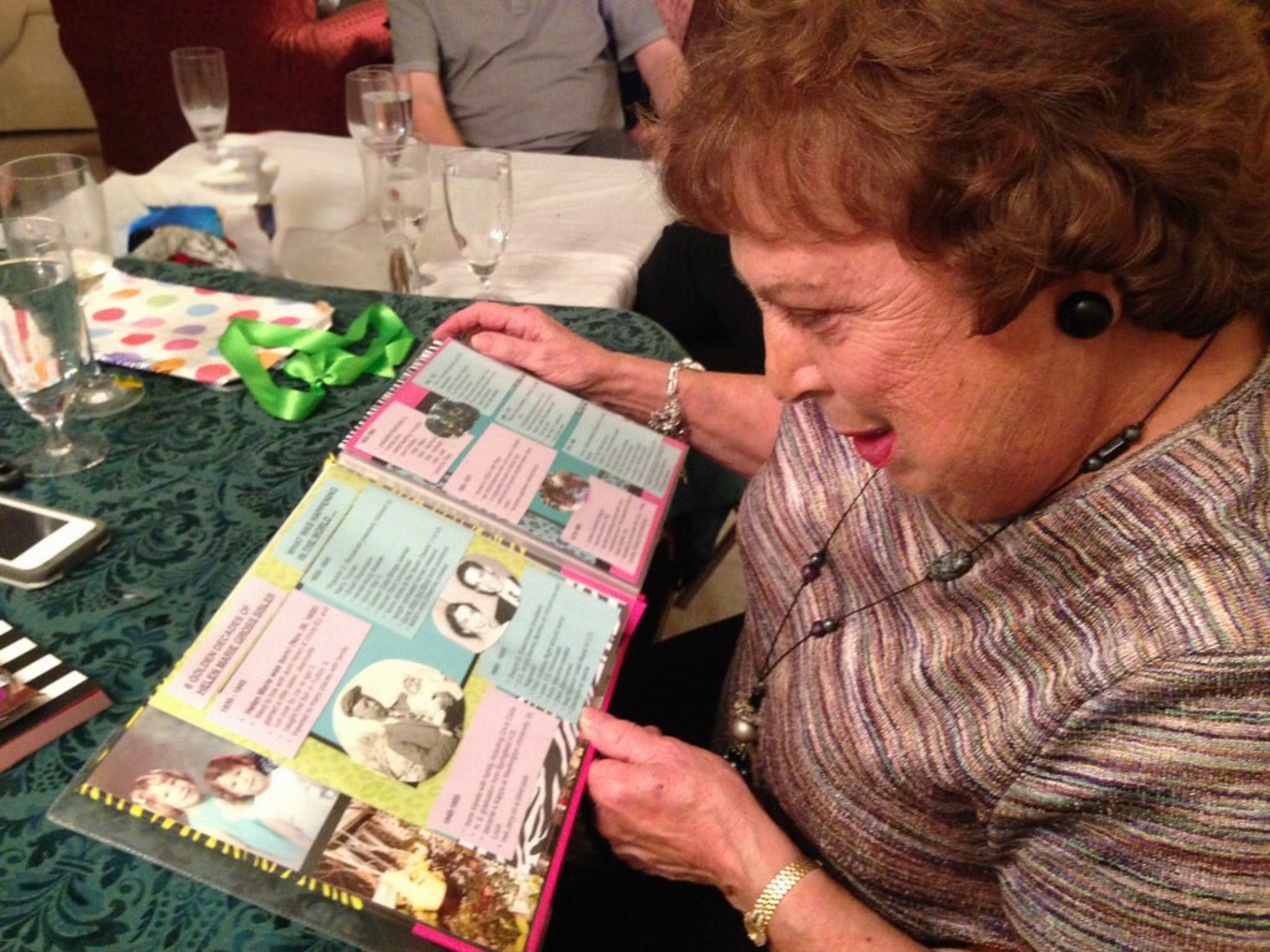

On my mothers nightstand was her bio and family history heavily annotated with photos. We would read and review these everyday, and some days she would remember, others not, but the books provided a bridge to her past and brought her peace. Good article, good advice.