The Mother Country

Our trip to Dublin, which began as a fact-finding mission, has itself become another story to tell over a dinner table. While some facts remain elusive, others provide a window into lives lived.

Our guest writer,

writes for her publication joins us as part of our first cohort in the Projectkin Members’ Corner. Monthly posts from members celebrate their contributions to family history storytelling — in all its forms. Posts may be written or recorded (audio or video) will be shared for free each month. Explore the entire Members’ Corner here.

Rounding Home

The trip to Dublin was my mother’s idea. At eighty-five years old, she wanted to see the town in Northern Ireland where her grandfather was born. Or rather, she wanted to see it again because she had already made this pilgrimage once, with her third husband. This time she wanted to go with her daughters, but only two of us could make it.

So in 2019 my mother and I flew to Ireland together, squashed into two tiny coach seats on an overnight flight. “Isn’t this nice!” she exclaimed before dozing off. My youngest sister flew up from her home in France and we took a train to Belfast, a bus to Portaferry, and walked around some cemeteries in the drizzling rain, talking family history. We were a cliché, really. Ireland is full of American tourists looking for their roots. EPIC: The Irish Emigration Museum was made for us.

Portaferry is an aptly-named harbor town in Northern Ireland, across a short channel from Scotland, where my mother’s father’s family had emigrated from in 1904. I had started researching our family trees in 1977, when Roots aired on television, but my mother had surpassed all my initial work to become a learned and obsessive comber of Scottish and Irish history. On this trip my mother was looking for her grandfather’s father: she knew only a name, William Espie, and that he was in the merchant marine. His birth, marriage, and death records eluded her, despite the explosion of digitized records that have transformed genealogical research. She already knew that William and Elizabeth Espie’s children (including her grandfather) had been baptized in the Portaferry Roman Catholic church, which astonished her because he had been a staunch Protestant when she knew him in the United States. On her first trip she had found a corrected death certificate for Elizabeth. The written record that a neighbor had filled out on April 10, 1879 was crossed off and below it Elizabeth’s daughter Maria had added her mother’s correct age and cause of death.

Revisiting the Past

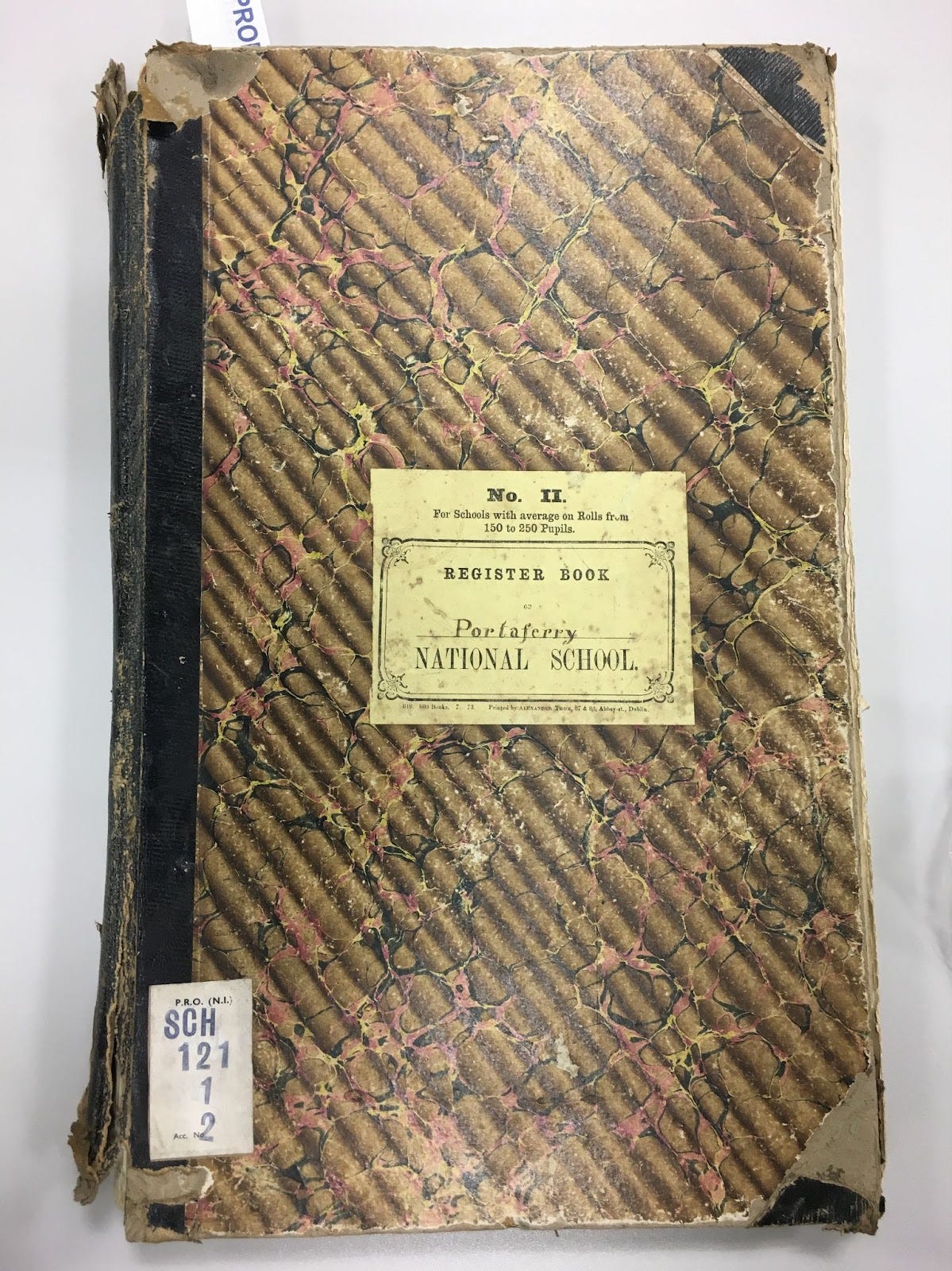

The genealogist we consulted at the Ulster Historical Foundation in Belfast on this return trip was intrigued by the corrected death certificate, which she said was rare. She wanted us to compare it with the microfilmed death records available at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) across the city—to confirm the dates. But as we made plans for our limited research time the three of us realized that none of us cared about the date. We didn’t need to know if Elizabeth had died on the 8th or the 10th. As a genealogist, my mother was more interested in filling out the tree, finding more relatives to pin to the right branches. As a professional biographer, I was more interested in unearthing personal records, more of that hint of personality and relationship in Elizabeth and Maria’s story. At PRONI, I lingered over the Portaferry National School records, in awe of the huge bound volume filled with handwritten dates and names of children long gone, their daily attendance and exams inscribed for the future unknown. What stories could be told between those lines? Unfortunately, not William’s or Elizabeth’s. We found some family names but not theirs.

At Portaferry we found that nineteenth-century school building and the approximate address where the Espies had lived. We waited for cemeteries to open and prowled around, searching for familiar names and trying to decipher worn inscriptions. But it was impossible to assemble a story from the stones and graves, except the universal story of time passing. The names and dates and relationships were barely visible.

Whereas most genealogical research is abstracted and vague—uncertain spellings and dates, unreadable handwriting and unidentified faces in old family photos— Maria Espie’s correction to the official record turned her mother’s death into a story, with characters and causation. Elizabeth was not aged 67, but 52. She died of a stomach disorder, not pneumonia. These details mattered to Maria and made the death an important part of her mother’s life—her biography, so to speak. These changes also tell us something about Maria. She knew the facts. She was intimate with her mother. With that bit of annotation, Maria joined the story too.

Genealogists have a necessary obsession with death, their primary data. Through death they push back generations into the next tier of the family tree. My mother had survived three husbands, and hanging over our trip, unsaid, was my mother’s own death, which will come too soon. It is imperative that she has a good old age, that my sisters and I spend time with her before she too becomes a story.

Living on in Stories

This year my mother turned 90 and all three of her daughters took her to Miami to celebrate. Why Miami? She had never been there. It was February and we were desperate for some sunshine. I brought with me a Life Story Interview Kit, a deck of cards for collecting oral histories. After dinner one night we sat in a circle in our AirBNB, taking turns asking my mother questions. It was surprising how much we learned, even from a simple question like “share your earliest memories.” I could see patterns emerging from her answers– a beloved brother who was sometimes a co-conspirator, a childhood moving from school to school, a history of thinking for herself that led her into a social work career. That brother has been gone for decades now, but lives on in these stories, as my mother will in her turn.

Our trip to Dublin, which began as a fact-finding mission, has itself become another story to tell over a dinner table. Many of the facts remain elusive, but others–like the annotated death certificate– provide a window into the moment the bare record of a life can come alive with meaning.

Do you think you might be interested in joining us here in the Members’ Corner with a piece of your own? We’d love to share your work. Learn more:

Victoria Olsen is a writer and biographer now working on a memoir about her father’s art career. She shares that work and other thoughts on family history and research on Substack in the newsletter From Life.

I love the quiet and methodical detective work of this story.

One of my favorite types of stories - living history combined with ancestry. Your phrase "before she too becomes a story" tugged at my heart and I am so glad you have the opportunity to spend time together. I also have ancestors in Ireland, finding more over the years, but DNA really broke open the doors for me to figure out exactly where they were from and who their immediate families were. I can not wait to go back now knowing where to plant my feet!